The Abundance in Scarcity

& Other Things I Learned This Week - 1/21/24

The Abundance In Scarcity

We spend so much of our lives trying to avoid scarcity. 12 hour days, 5+ day weeks, delayed gratification, trying to build towards a life of abundance, one where scarcity has no place in our dictionary. The mere thought of scarcity scares me - the thought of not having enough money, enough food, enough health drives me more than I'd care to admit. This leads me to plan my life to minimize the possibility of scarcity - always saving enough, always consuming less than I need, taking on as little leverage as possible, to ensure that when that rainy day does come, I have more than enough to not be worried.

Some of my recent reading has me questioning this mindset, though. Is scarcity really all that bad, and could there be an upside to designing scarcity into our lives?

In the same way that the thought of scarcity can be a driving force, I've started to wonder whether the embracing of scarcity could be an even more potent force, one that if managed well can be harnessed to maximize our potential and outcomes.

As one looks back in time, it's hard not to see the link between scarcity and progress. Often, it's the eras during which countries and individuals have dealt with the biggest existential threats from which we've seen the greatest amounts of human progress.

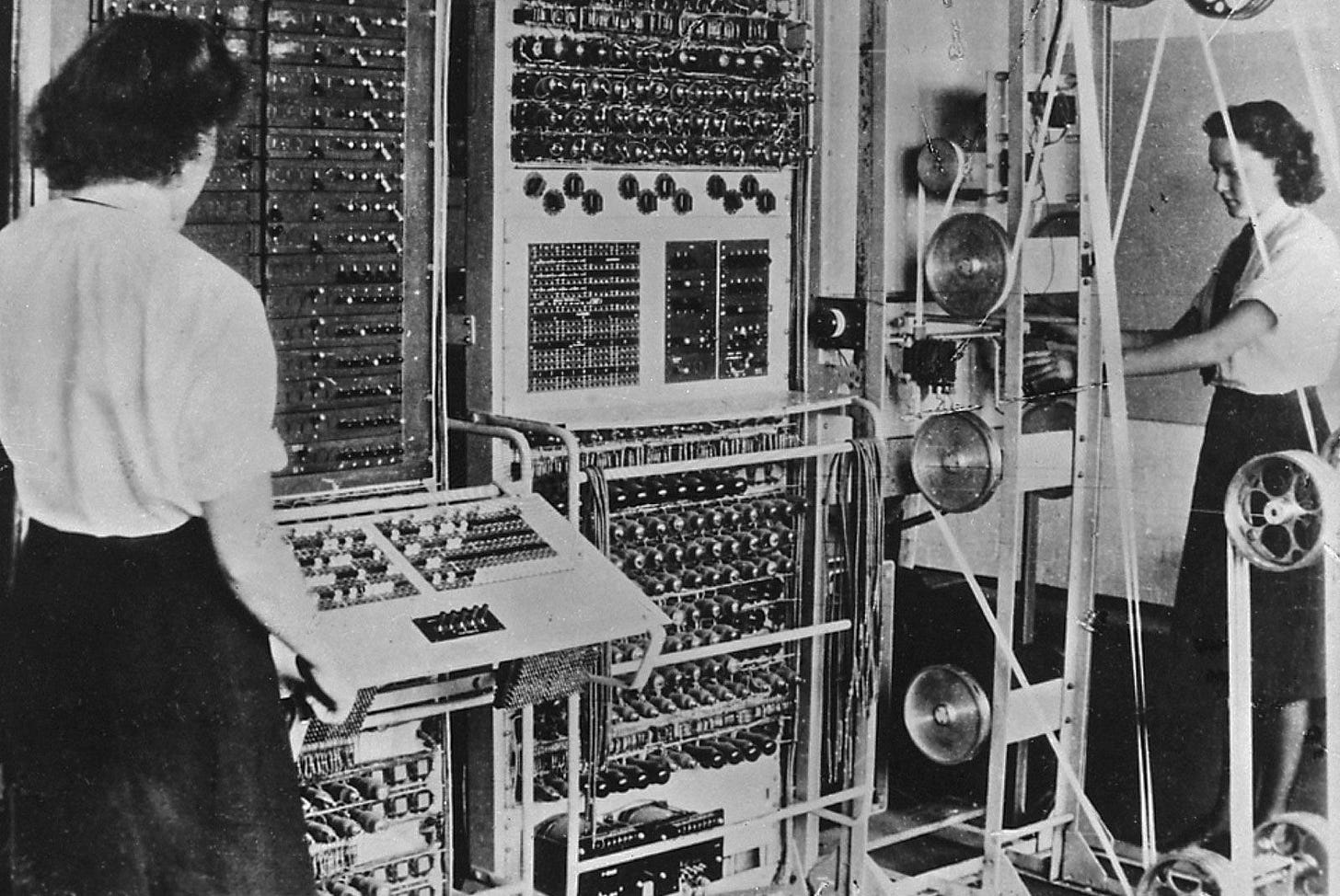

The innovative effects of wars are well documented ("War is the Mother of Invention", as one quote goes). The first computers were created during WWII to help submarines automate targeting and to decode German encryption. Our knowledge of farming expanded with (tragically devastating) experiments and use of biochemical warfare, leading to the modern day pesticides which dramatically expanded our ability to feed the world's growing population. The flu vaccine and mass-produced penicillin were some of the many other innovations that were enabled by WWI and WWII respectively as the ability to keep soldiers happy. Critical innovations that have come to define mankind and our progress.

Source: Britannica. The Colossus, the British WWII Codebreaking Computer

Can scarcity be used as a competitive edge, though? With wars, scarcity is shared by all parties - and when something is shared by all parties, it can't be an edge. With wars, too, scarcity comes at a huge cost, of lives, of economic focus, of physical destruction. If we can only harness scarcity when we inflict huge loss on ourselves, certainly that can't be worth it.

I've been intrigued, however, by the advantage that relative scarcity can bring.

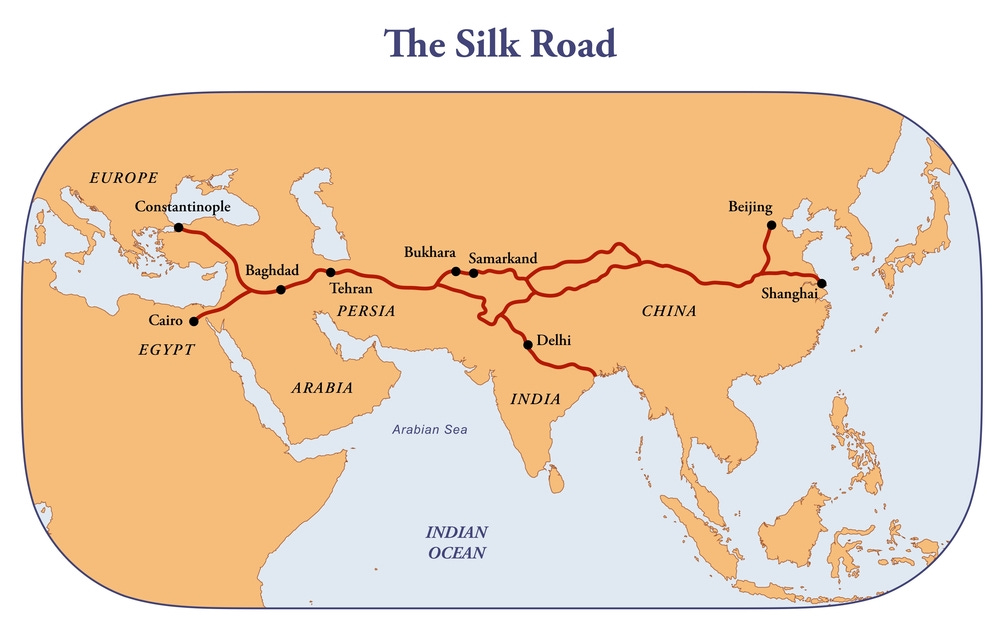

Take Western Europe, for example. In the 14th and 15th century, Western Europe was considered the backwater of the world. At the time, the main trading corridor of the world was the Silk Road, which ran from Shanghai (China) to the east and Cairo / Constantinople (modern-day Turkey) to the west. Global commerce and power was concentrated in the hands of China, India, and the Ottoman Empire (Turkish Empire).

Source: IFL Science

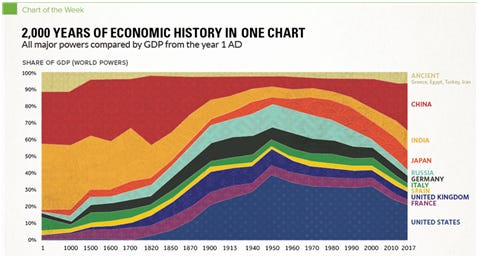

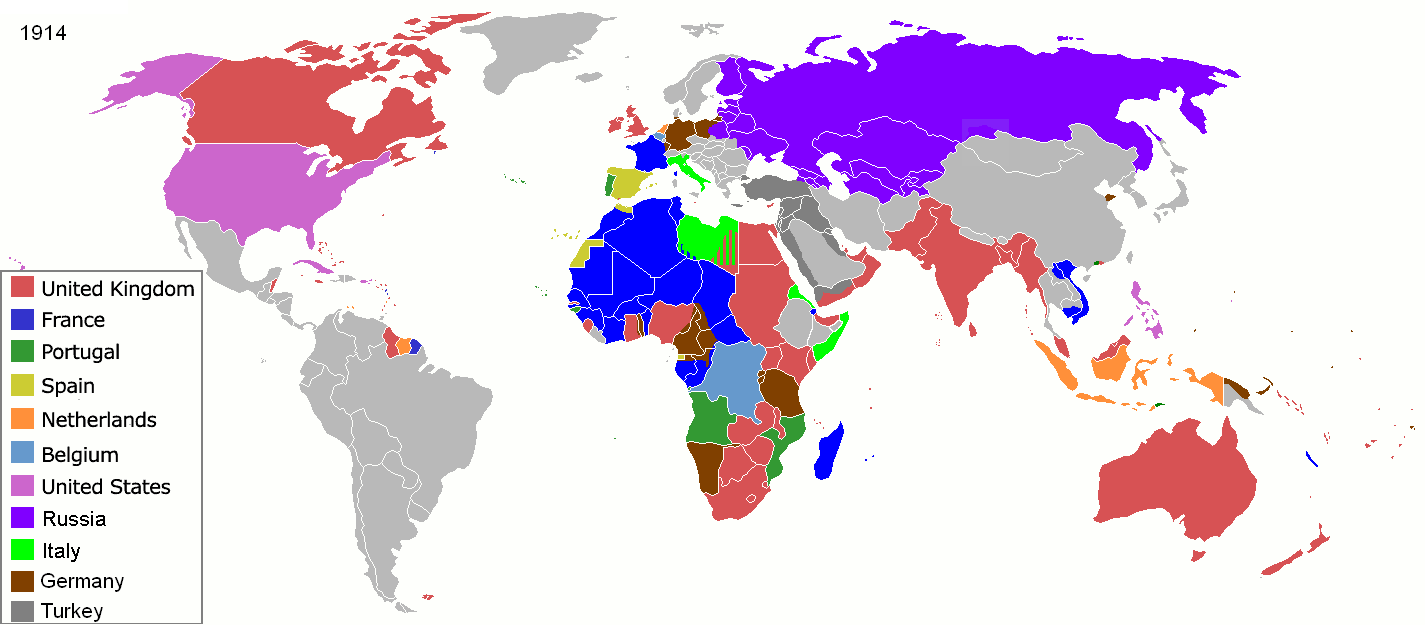

The Western European nations of France, Britain, Spain, Netherlands on the other hand, lacking access to these very valuable trade routes, had economies that paled in comparison to the global superpowers of those days - in the 1500s, India, China and the ancient empires of Greece, Egypt, Turkey, and Iran (yellow, red and orange in the chart below), together were ~70% of global GDP:

Source: Visual Capitalist

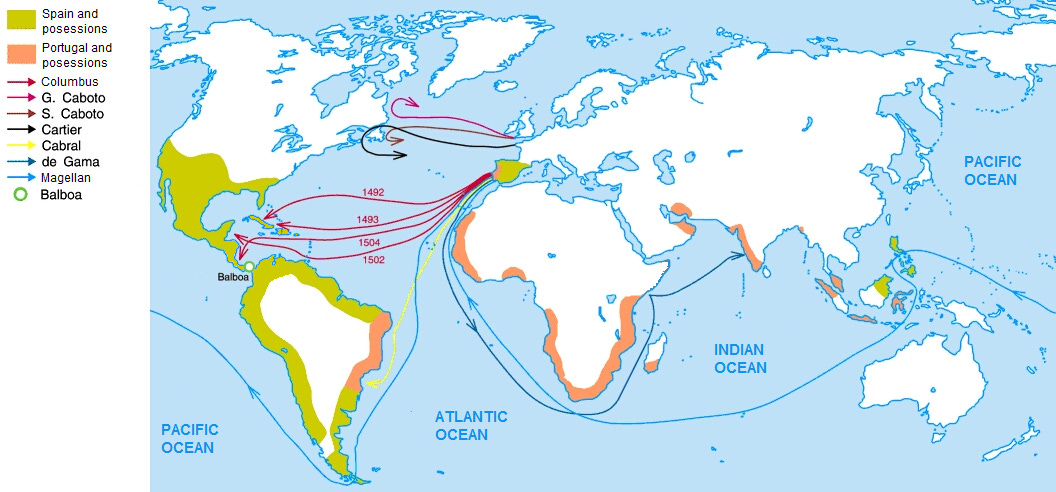

Western Europe in the 14th and 15th century was a picture of scarcity - lacking trading partners and natural resources. This scarcity, however, eventually became their competitive advantage in the same way the relative abundance of the Ottoman, Chinese, and Indian empires became their weakness - in looking for the resources their economies needed, Western Europeans were forced to go seaborne. They took and paid for the necessary risks for seaborne expeditions south along the coast of Western Europe, finding their way to Africa (1400s), and eventually, after significant trial and error improving their seafaring capabilities, to America (1500), and finding their way around the African Coast to India, Southeast Asia, and Australia.

Source: Wikipedia - Spanish and Portuguese seaborne voyages

This opened up seaborne trade routes to areas that were still relatively untouched by the powers of the time, fostering trading relationships and eventually, in many cases, leading to colonialism. And colonialism, and the access and exploitation of the lands and people that it entailed, undoubtedly played a large role in the massive growth in Western European economies and power in the centuries that followed. While there were many other reasons that enabled the Western Europeans to dominate these "newly discovered" lands - see Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond - absent the relative scarcity of Western Europe of the 14th and 15th century, there would not have been the resolve necessary to develop the naval competencies that they did that eventually enabled their rise to power. In scarcity, eventual abundance.

The resulting (relative) abundance seen in many of the Western European nations eventually led to a key weakness that ceded power to another nation in the late 1800s and early 1900s that had not participated equally - Germany. Germany had no colonies until the late 1800s, and when they eventually did obtain colonies, they were left only to parts of Africa, unlike neighbors the UK, France, and the Dutch, who by then had control over (and in some cases eventually lost control over) much of the rest of Africa, Southeast Asia, Australia, and the Americas.

Source: Wikipedia

For much of history, textiles were a crucial industry for many of the leading global powers. As important as the actual manufacturing of materials for textiles was sourcing the dyes to color the clothing that textile mills were producing. Until the mid to late 1800s, dyes were produced from plants and fungi, many of which were native / abundant in colonies that the British and French had access to. Unfortunately for Germany, with little access to colonies, dyes were an expensive input as they had to be imported, which limited their ability to compete in the textiles industry. Scarcity.

This scarcity, however, led to a serious need for innovation for a country that was until then, the backwater of Europe. Eventually, this led German scientists to discover synthetic methods to produce dyes from coal tar, kickstarting the Germans' march towards European dominance. In 1860, Germany imported almost all its dyes. By 1877, less than 20 years later, Germany accounted for half of world dye production - a massiveboost to its economy. More crucially, the methods and learnings that were perfected from the dye-making processes were eventually used to discover other synthetic chemical production methods, kickstarting the German chemistry industry, which remained a global superpower for many years (thankfully, just economically and not militarily). Many of the companies that started on the back of these synthetic dyeing processes remain large corporations even today (Bayer and BASF, to name two).

Despite the riches and power of the other Western European nations, their abundant access to dyes likely led to complacency, driven a lack of willingness and incentive to innovate. In doing so, they eventually ceded a big portion of future economic opportunity to a competitor. Not an outcome one would immediately expect given the abundance of resources available to them, but again, scarcity enabled innovation that eventually supplanted and outcompeted the status quo. In scarcity, we find eventual abundance.

Say what you want about Elon Musk, but I suspect that he uses this to his advantage in running his companies. It perpetually feels like one (or more) of his companies is in full-blown crisis mode. We all surely recall the news stories of Elon Musk sleeping on the Tesla factory work floors - such radical behavior for a CEO, but when you think about it, a genius move, perhaps? He has been quoted saying that doing so would act as an inspiration for his employees to "give it their all". In instilling in employees that there is scarcity, not abundance, he is eradicating abundance and complacency from the culture, forging a shared sense of fighting for collective survival, that pushes individuals and teams to work harder than they otherwise would. Perhaps that's given his companies the edge they need to outcompete established competitors? Perhaps that's why so many incumbents eventually fail?

Of course, this isn't always the case, as there are many other instances where abundance and early leadership compounds over time, and scarcity is debilitating. I'm merely making the point here that in some cases, scarcity can be used as a useful tool, weapon, and motivator to trigger progress. Exactly which scenarios we'd prefer abundance vs scarcity, and how we can use this scarcity to make ourselves better and optimize our outcomes - that'll be a topic for another week.

The Utility Curve of Money

Listened to this very insightful podcast this week. It posed an intriguing question, which has captivated my thoughts for the past few days:

Given a choice, would you rather be 90 years old with $100 billion or a penniless 20-year-old?

My answer came swifter than I expected. I'd rather be 20 and have my whole life ahead of me, even with no money, rather than be 90 with all the money in the world, but no time left to spend it (assuming the $100 billion can't extend by life by another 50 years, of course).

This raises an interesting proposition, that the utility (value) of money to us changes over time. Money isn't worth that much to us when we are born, since we can't spend it, so for the initial years of life, the utility of money grows. At some point though (maybe when we are 40? 50?), the utility of money peaks for us, and begins to decline. For as we age, we have less time to spend the money we have, but also are less physically able to do so (no skydiving at 70!).

Plenty of implications to this that I want to reflect on over time, but I do think it's a good reminder that while saving is a good thing (and I do think the average American does not save enough), there are limits to saving too much, and that we can forgive ourselves for spending more money than we would be comfortable, especially on experiences that we can only do in this current season of our life, experiences that add color and fulfillment to our lives. As I move into a transitional phase of my life where I have more time (even as I have less short-term earnings power), a good reminder that I should take advantage of the time and flexibility I have on my hands and do the things that future me will regret not doing.

--

That's it for this week - thanks as always for reading!