The Power Of Symbiosis

& Other Things I Learned This Week - 1/7/24

Life is short, but we can be optimistic

The 2nd half of 2023 was a brutal one. Getting hit with bad medical news about friends' loved ones – cancer in a teenage daughter, a wife, a father – in a year where I had a brief cancer scare myself was tough. Cancer is such a scary, scary word to hear, one so closely tied to death, one we've seemingly been fighting forever to no avail. In many of our psyches, it's often seen as a death sentence, one made even scarier by the fact that often there is often no cause-and-effect answer to explain why someone gets cancer. It just happens.

This fear isn't surprising, as so many cancer stats out there are horrific at first glance. Since 1990, the number of cancer deaths have increased 75%. Our likelihood of contracting cancer in our lives seems to be rising - estimated by the NHS to be 1 in 2 people, where I was 1 in 3 or 4 people in the past. All incredibly frightening stats.

Ultimately, however, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic, or at least, not be too pessimistic.

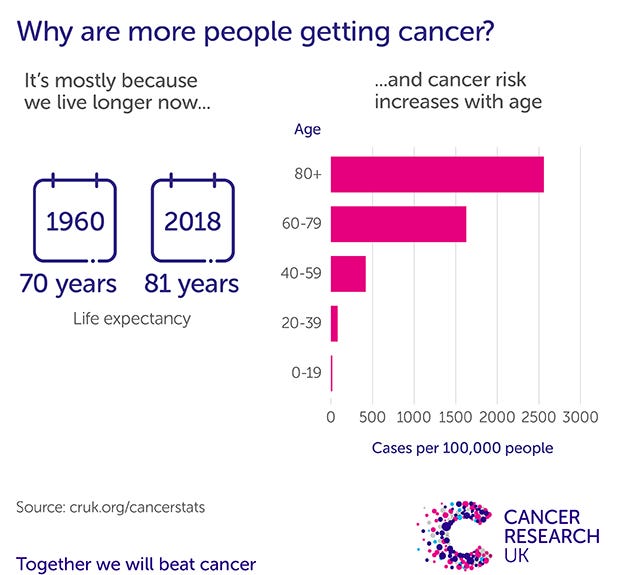

Most cancers are ultimately a disease of old age, when our cells lose the ability to regulate their own division, and start dividing uncontrollably. As we've gotten better at treating many of the diseases that were the biggest human killers in the past (e.g. cardiovascular health) and more of the population survives into their old age (life expectancy increased from 64 years in 1990 to 71 years in 2020, a whopping 10% increase in just 30 years!), it's inevitable that cancer rates rose (and will continue to rise) as more individuals made it in to the age range at which cancer risk is higher:

I also suspect that increased cancer rates can also be explained by improvements and frequency in cancer screening and detection - this renders the signals from comparisons between the past and the present tenuous at best. Simply, more testing equals more cancer detection; however, this doesn't tell us whether more people will in fact die from cancer. In fact, there are a number of cancers that people more often die with than die of (e.g. prostate cancer). There have also been many instances where screening programs drive more cancer detection, increasing the cancer rate, but eventually don't improve mortality. In South Korea, for example, a national thyroid cancer screening program caused diagnoses to increase 15x between 1993 and 2011, however mortality did not change despite a more aggressive and proactive treatment regime. This calls into question our natural instinct to believe in correlation between cancer rates and cancer deaths; cancer rates are therefore ineffective proxies to judge progress in the fight for cancer. What matters most, therefore, is cancer death rates - as it is the death that we fear, more so than the disease.

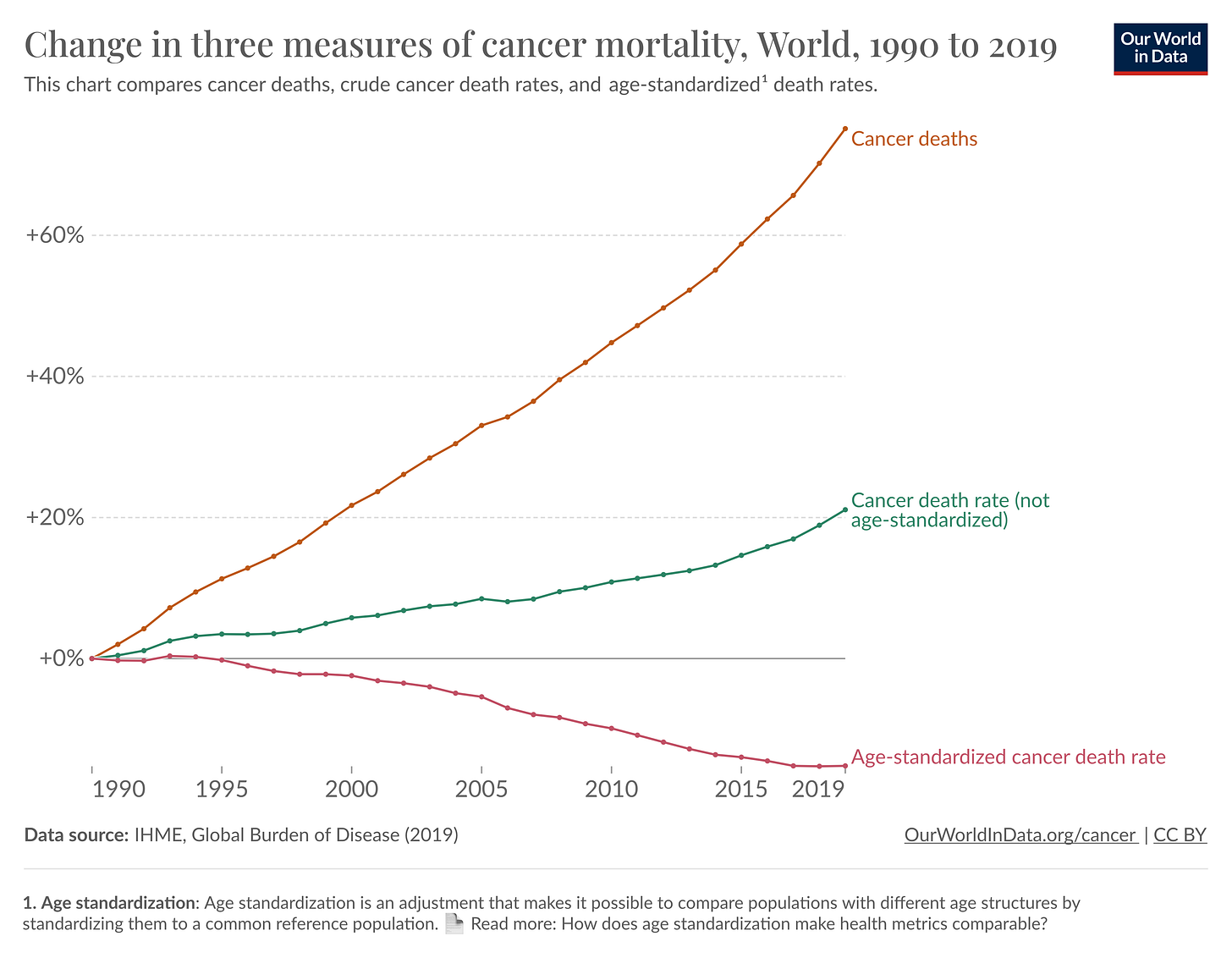

The dramatic 75% increase in cancer deaths since 1990 is made far less scary when you use the 100+% rise in the non-working population (65 and above) since 1990 as further context. A population that ages will naturally have more instances of an age-related disease. The chart below shows that while cancer death and cancer death rates have increased, when adjusting for population age mix, the death rate from cancer has actually declined 15%, an optimistic signal even if one could argue that the 15% could be higher.

Having gone down a bit of a rabbit hole the past few months on molecular diagnostics and how they can influence screening and treatment, I’m also very optimistic about the innovations in the R&D pipeline to improve our cancer-fighting toolkit. Every cancer diagnosis is slightly different, i.e the mutations that occur in cancerous cells will differ from patient to patient. We are getting better at finding specific tools to treat specific cancers. No longer are all patients who have lung cancer getting the same treatment - a blunt weapon against a targeted enemy. Doctors can today quickly figure out the mutation a patient has, and then prescribe a drug that specifically targets that mutation, dramatically increasing survival rates. The mechanisms of delivering the drug are also improving, with new therapies using your body's own immune system to go after the “bad” cancer cells. Companies like GRAIL are also working on better ways to screen for cancer, via blood tests that purportedly test for over 50 different cancers. These diagnostic innovations should eventually bring us down the cancer diagnostic cost curve, enabling widespread early detection, when cancer is far less deadly and more treatable.

The final reason for us to be optimistic - a substantial number of cancer deaths each year are due to factors that we can control. It blew my mind that 45% of cancer deaths in the US - that's close to 300,000 people each - are the result of risk factors like smoking, obesity, alcohol, physical inactivity, and UV exposure. Not the time to debate whether factors like smoking, obesity, and alcoholism are truly "controllable", but it heartens me to know that there can be some fixes that are more easily controllable than the other 55% that we are more helpless in preventing.

All that said, a timely reminder for myself that life is short and that there is so much volatility in outcomes that are outside of our control. My dad often told me that 90% of life we can't control and the other 10% is how we react to the 90%. That 10% is precious and all we have; we must do what we can to make the most of it and not lose agency of that 10% to other forces. Otherwise we default to being a cog in a machine. What would we be living for, then?

Symbiosis

Been spending the past few weeks reading Origin Story by David Christian, which explores the history of everything, a field known as "Big History" - from the big bang all the way to modern civilization. Many takeaways I'll share over time, the most prominent right now being the importance of symbiosis.

Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and natural selection has influenced how so many in the world (me included) think about how the world got here. The "survival of the fittest" narrative promotes that idea that therefore we, as individuals, must continually strive to be the best versions of ourselves to survive in the world. We must work to be faster, stronger, smarter - and only then can we be an evolutionary "winner". Individualism at its finest.

What Origin Story makes very evident is that natural selection is so much more than the strength of an individual in isolation. Everywhere you look in history, it isn't the solo individual that survives - rather, it's the ability of an individual to form symbiotic relationships with others - whether intra or inter-species - that allows it to outcompete others.

This is everywhere. Electrons, protons, and neutrons formed symbiotic relationships with each other to form atoms. Atoms group together to form molecules. Molecules that moved up the complexity ladder by cooperation to become the first cells. The first eukaryotic cells (more complex cells) were likely formed as a result of a symbiotic relationship between distinct simple cells (prokaryotes and eubacteria) - which explains why we see bacterial DNA in many parts of eukaryotic cells (e.g. mitochondria, chloroplasts). Cells evolved into multi-cellular, complex organisms that eventually led to humans. Humans banded together when resources got scarce to form farming communities. States, which were collections of different farming communities, outcompeted the smaller, informal farming communities. The eventual collection of states into countries - the bigger they are, the more dominant on the global stage. At each stage, the banding together of individual entities (regardless whether the individuals are homogenous or heterogenous), with the right regulatory system, creates a new "being" at a higher trophic level that easily outcompetes smaller, less complex entities.

Intriguingly, it seems that symbiosis, rather than the strengthening of the individual, has been a key driver of evolutionary fitness. Rather than concern itself on being stronger, faster, or smarter, an individual just has to find a way to be part of these collective "beings". Mere association with these fitter collectives allows the individual to persist given strength in numbers. But of course, to do so, it has to prove to the collective that it belongs, and this requires bringing something to the table to enhance the collective's functioning and success. Hence the symbiosis - the individual needs the collective to succeed, and the collective needs the individual to succeed. When symbiosis works, all parties involved benefit. In the same way that the first domesticated cows, pigs and chicken proved themselves as superior farm animals, which allowed them to grow alongside humans for thousands of years as they plowed our lands and fed our mouths - today, the weight of domesticated animals today exceeds all non-domesticated animals by almost 25 to 1.

Symbiosis also drives rapid change and progress - whenever new and novel collectives form, such as when we formed the first complex eukaryotic cell, or the first state, we see a substantial "leaps" forward in capabilities. Think about what a state can do that an individual can't (e.g. mobilize an army, innovate). And what a multi-cellular organism can do that a single cell can't (e.g. read, analyze).

In fact, many of the best businesses in the world are enablers of and/or beneficiaries of symbiosis.

Network effects, at the end of the day, are the business form of symbiosis. Where being a participant in a network confers access to parties, goods, and services, that one would not otherwise have access to. Think Amazon, or any other marketplace, and how they enable the matching of consumers wants’ to producers’ capacity - Amazon offers producers reach, while offering customers options. Every party is better of as a result of the platform. Symbiosis.

Horizontal integration, and the "one-stop shop" strategy, too - when successful at combining two or more different but complementary products, each product can be strengthen beyond its own limits. The Apple ecosystem of products, for instance. The iPhone, AirPods, iPads, Apple Watches - on their own, decent to great products. Together, they make each other better and build up an incredible ecosystem that is hard to leave.

On a personal level, this is a reminder that self-improvement, while important, has its limits. And it is only in building out a network of symbiotic relationships - both with likeminded and non-likeminded individuals - that one can enhance their evolutionary fitness. Lean on those who you can get value from, but also those who you can provide value to. When you grow, they grow. When they grow, you grow. Keep looking for your symbiosis, for it is in leaning on others that you can maximize your own potential.

Avoiding Capital Losses

There's an old adage in the stock market that goes: "time in the markets beat timing the markets". The idea is that rather than trading the market, we should just leave our capital in the market, given 1) it's close to impossible to time the markets, and 2) there's substantial tax leakage for traders, which leaves anyone trying to trade in and out of the market quickly worse off.

While I largely abide to the adage, there have been moments in time when I've seen trying to time the market work out. Case in point: As markets were tanking in March 2020, I recall a colleague mention that in his experience, one should run from markets that swing +/- 5% in a day. He took all his money out, likely at around $320/share of SPY. As a result of this, he was able to avoid the next drop from $320 to $230 (30% drop!). While he likely didn't manage to re-invest his entire net worth back into the market at the $230 lows, it did make me wonder whether there was ever a point where timing the market made sense.

I spent some time this week trying to figure it out. This thought exercise involved considering the level of expected share price decline at which we would be willing to pay the capital gains tax leakage.

A refresher: the reason that capital gains tax leakage matters is that whenever one sells a stock with capital gains, the capital gains taxes they pay to the IRS permanently impairs their capital base. Two examples:

Sell then re-buy: Assume you bought 100 shares in a company stock at $1 each. The stock rises to $2/share. If you sell the stock at $2, you would get $200 of proceeds, but pay $20 (assuming 20% capital gains tax) to the IRS. This leaves you with $180. Now, if you were to re-buy the stock at $2/share, you will now have 90 shares. If the stock further doubles to $4, you end up with shares worth $360. Selling those shares will yield $324 of post-tax proceeds ($180 + $180 x 0.8).

Hold through sale: Now, same scenario but assume we did not sell. By the end of the investment, we would get $400 of pre-tax proceeds, and $340 ($100 + $300 x 0.8) of proceeds.

The $16 difference between the two examples is the tax leakage associated with capital gains taxes. It happens because by paying to the IRS the $20 of capital gains taxes, we effectively forfeit the incremental upside associated with that $20. The $20 would've grown to $40, of which we would've received $16 of incremental post-tax profits. Painful.

Is there a threshold where you'd be willing to pay up for this leakage, to avoid capital losses? Certainly, there is - since if you thought that shares were headed for $0, you'd be willing to pay up for the capital gains at any point as that puts you in a better position than if you got nothing at the end of the investment.

But what is that threshold? At a very basic and qualitative level, the threshold should be when your expected avoided loss is equals to the value of the tax leakage that you'd have to put up with. In the example above, if at $2/share, you thought your loss was going to be greater than the $16 of tax leakage (i.e. $0.16 decline in share price, or 8%), then you would sell the shares at $2, and buy it back when it is below $1.84. Anything above that and you would be in a worse off position.

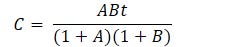

Is this indifference point always 8%? Nope. I did the math, and got to the following equation, where A = retroactive capital gains, B = prospective capital gains, C = expected near term loss, and t = capital gains tax rate:

Studying this equation, you can see that the threshold (C) is determined by 1) the size of prospective and retroactive returns, and 2) the size of the capital gains tax rate. This makes sense, as the larger your expected or unrealized returns, the larger your tax leakage will be. Vice versa with the capital gains tax rate.

You'd notice that as A or B gets really large, C converges to t. This is helpful for our rule of thumb - you should only sell if you think that your expected loss (C) is larger than your marginal capital gains tax rate (usually 15-20% federal and up to 13% for state). Anything below that and you are possibly making an uneconomic decision.

A reminder that short-term capital gains equals your marginal income tax rate, which for some can approach 50+% - this means selling to time the market will require an expectation that you will be able to buy the shares back more than 50% lower, which if you're SPY investing, has only happened a few times in history (GFC, dotcom crash). Be really, really careful when you’re doing so.

Quote of the Week: "Study the world rather than what has been said about the world” / The Power of Confidence

David Christian wrote the above in Origin Story, while considering how humans went from mainly believing that the earth was flat, floods were brought by the gods, and other myths passed down through word of mouth over time, to questioning the myths and trying to understand the world and why it was how it was. It was a profound shift in the human psyche that led to the acceleration of innovation.

Christian theorizes that Europeans, fresh off their discoveries and conquests of America, gained more confidence that they had the world in their grasp. This created a sense of European-exceptionalism, which gave them the confidence to ask questions that they previously had assume were beyond their abilities as mere mortals.

It’s an interesting thought - as much as we have the tools at our disposal, we need to believe - truly believe - that we are worthy wielders of those tools before we can use those tools effectively. Perhaps the bedrock of innovation and creativity, after all, is just that - the right psyche. Daring to believe.

But also, a reminder that primary diligence is invaluable. I’ve learned the hard way often enough, trusting others and their diligence given my beliefs in their intellects. Ultimately, however, humans are fallible, and just because someone is more experienced, intelligent, or a story has passed down through the generations, doesn’t mean they are right. Our minds are the only things we have, and if we don’t trust it and learn to work with it, and instead trust that of others, then what does that leave us with?

----

That's it for this week.